Reduction of C++ project build time - Introduction

Hiho! It’s high time to brush the dust off of this blog once again. This time I will ramble about C++ build times. Do not expect this series to be uber formal - it’s more of a “food for thought” kind of thing.

Why you might care

While we pay relatively little attention to how our work is turned into bits and bytes (usually it occurs only when compiler screams back at us), high-level overview of build process and proper maintenance of project structure`s hygiene can have positive impact on our day-to-day job experience:

- Code could become faster to build…

- … And (compared to carelessly maintained project) it`s build performance might not deteriate nearly as fast over time.

- As a result, the throughput of CI pipelines (that are hopefully in place in your project) increases.

- Faster builds might make testing bugfixes under the debugger easier due to shortening time needed to perform one iteration of compiler-programmer feedback loop - since the code`s compile time is reduced, the time needed for compiler to verify it`s correctness is reduced. As a result the changes are easier to verify.

Having said all of that I must mention that build time improvements are not a free lunch - as we will see in forthcoming articles they often require making tradeoffs between build-time and runtime performance (or other resources, such as code size). Some of the techniques that might be helpful in reducing the negative impact of presented changes will also be showcased. This post introduces terms and concepts required to understand the problems and optimizations applicable to build process.

Build process overview

Disclaimer: A phrase “C/C++” might be used over the course of the following section. For the sake of this discussion I view C as subset of C++, because all of the build-time reduction techniques applicable to C can be used in C++ - the opposite is sadly not true.

C/C++ build process has three stages - preprocessing, compilation and linkage. Before diving into them though, let`s start with the notion of “translation unit” - which is a term that will pop up in this series pretty frequently. Translation unit is an output of preprocessing stage for a given source file. Thus, it is the final input of a compiler.

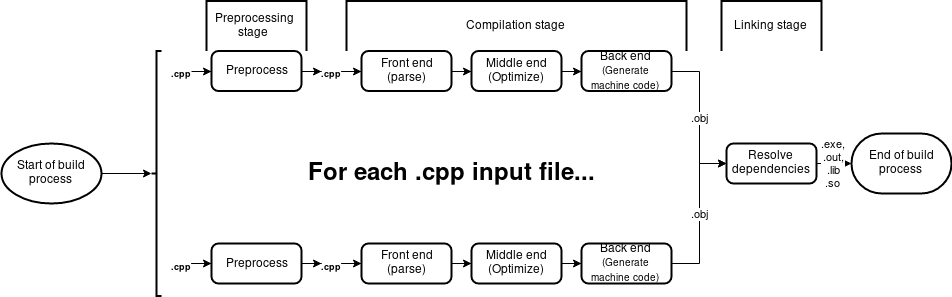

From a high-level perspective three stages of build process can be described as:

- Preprocessing - an optional process that accepts a source file as it`s input and produces another source file (translation unit) as a result. C++ preprocessor is fully compatible with C one.

C preprocessor can:

- Replace tokens in the source file with a predefined set of values (macros) - this is achieved via #define directive.

- Conditionally remove parts of text file based on preprocessor state - also known as #ifdef, #indef directives.

- Embed other source files within the source file - or just #include directive.

- Compilation - translates each translation unit into object files. An object file contains machine instructions. Additionally a compiler might optimize output machine code. Note that the result file is not yet executable at this point - this is responsibility of a linker.

Compiler structure is generally divided into two parts - frontend and backend. The former is responsible for parsing the source file and translating parsed code into an intermediate form that’s understandable by backend. The latter takes foremenetioned intermediate form, (optionally) optimizes it for given platform and generates machine code. There could also be a middle end between the two forementioned parts - it can optimize code in platform-independent manner (for instance by folding constant literals - statements like

500 + 3can be resolved to503at compile time, thus eliding the computation at run time). - Linker - resolves dependencies between translation units that participate in a build process. An example of a dependency between two translation units would be the call to function defined in other .cpp file. Linker also produces the final output file. Linker`s input consists of all object files that were produced by the compiler in the preceding step.

As we can see the path from .cpp to .obj can be parallelized (assuming no system-wide resources that are required by compiler). Soon we will see whether that can be exploited.. :)

Deceptive #include statement

The #include preprocessor directive includes source file (identified by it`s first and only argument) into the current source file at the line immediately after the directive (source: cppreference). It is pretty deceptive in a way, because what we see in the source is not what we get - a 5 line .cpp file can be expanded to thousands of lines of actual source code. The contents of included files are compiled like any other code. While it may seem obvious (it is #include after all, right?) I feel that it is easy to get wrong. Header files should be as tidy and fine-grained as possible.

What is inlining all about?

Inlining a function call means replacing the call instruction with actual contents of a function - thus improving program performance. Of course not every function call can be inlined - for starters current compilers use heuristics to determine whether the call should be inlined, because doing so introduces additional program size overhead. Additionally it is only possible to inline calls to functions whose definition is present in current translation unit. Hence any function call that has to be resolved by linker is impossible to inline (barring LTCG - we will get to that in a second).

#include was mentioned a few phrases prior to this one, because it (indirectly) allows to inline some of the function calls. For instance it is common practice to put function templates in header files. Since this template lands in the source of it`s dependents, the compiler can inline the call to the function.

Hello LTCG - link time code generation

Recall that in order to inline a function call compiler must have access to the function definition in given translation unit. Hence the function we want to be inlined has to be accessible in the translation unit. This can lead to bloat - if the same function is “costly” to compile (it`s compilation from front end through back end takes quite a lot of time), then each translation unit that depends on it has to pay the price of building said function. This is the opposite of reuse. However, apparently cookie can be had and eaten at the same time.

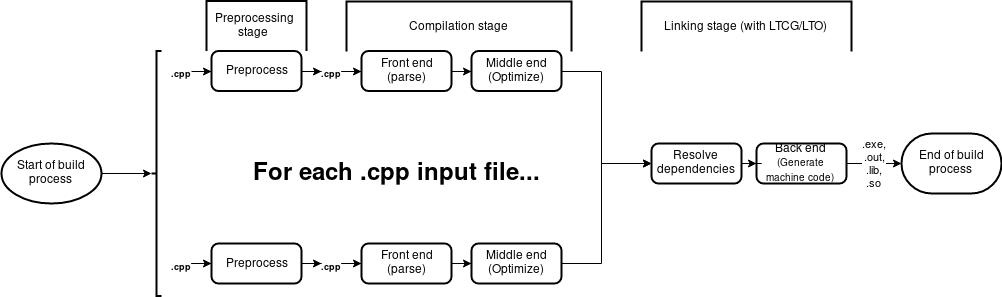

Link Time Code Generation is a technique which - as the name suggests - delays code generation part to the link time. Thus various optimizations (among which is inlining function calls) can be applied to whole codebase. Contrary to compiler, linker has access to whole codebase - hence it does not have to emit a function call when inlining it would be fine too.

Why would I bring that up though? One of the things that shall be addressed in future parts of this series is dealing with redundancy. Heads up - fighting it might have negative impact on program performance due to the reduced possibilities of inlining function calls… which is exactly what LTCG is good for. While LCTG should not improve build times substantially (I guess it might actually lead to slight decrease) it is worth employing to reap benefits of good performance at both runtime and build-time.

Takeaways

Today we addressed the build process (from a very high-level perspective). Hopefully it is a good foundation for future parts of this series. As with most things, reduction of build times is a game of tradeoffs. It is important to understand what these tradeoffs are and whether this mouse is worth chasing. In the next post I will address techniques useful in reducing the impact of templates on your codebase. Stay tuned!